The paperback of Barbara Kingsolver’s book Animal, Vegetable, Miracle: A Year of Food Life has a blurb from Rick Bass on its cover that reads: “This book will change your life. . . . Perhaps never before has [food] been written about so passionately.”

When I first saw that, I thought: I guess Rick Bass has never read a book about food before.

Then I read the book, which I absentmindedly picked up in a used bookstore on vacation at the end of August, where I ran into someone I went to grad school with, which was fun and small world-y but also, like, where else are you gonna find two writers but in the three-dollar bookstore thumbing through trade paperbacks and, in my case, tomes about decorating loft apartments?

After starting Animal, Vegetable, Miracle to kill time while Samantha napped – and because I was not quite up to the copy of Moby Dick I also bought – I was quickly sucked into the world of Barbara Kingsolver, a writer I think of as, basically, vegetables for your life. When I read High Tide in Tucson sometime in my pregnancy (or was it after Samantha was born?), I could not get out of my head Kingsolver’s moralizing, maternalistic tone: We are all connected. Another person’s trash and/or bad ideas are your responsibility, too. Do not turn your head, do not shirk your duties, think like a sane person and act like a kind one.

The book is full of recipes, cheese-making tips, and canning summations. It gives voice to Kingsolver’s longstanding gardening habit, introduces her animal husbandry forays, and somehow makes the thought of buying a food-dehydrator feel like a no-brainer. It is also full of quiet, simmering humor, the kind that walks right beside a wide lens on the world.

About mulching the garden she writes:

“My favored mulching method is to cover the ground between rows of plants with a year’s worth of our saved newspapers; the paper and soy-based ink will decompose by autumn. Then we cover all that newsprint – comics, ax murderers, presidents, and all – with a deep layer of old straw. It is grand to walk down the rows dumping armloads of moldy grass glop onto the faces of your less favorite heads of state: a year in review, already starting to compost.”

About the act of weeding, she writes:

“It is also noiseless in the garden: phoneless, meditative, and beautiful. At the end of one of my more ragged afternoons of urgent faxes from magazine editors or translators, copy that must be turned around on a dime, incomprehensible contract questions, and baffling requests from the IRS that are all routine parts of my day job, I relish the short commute to my second shift. Nothing is more therapeutic than to walk up there and disappear into the yellow-green smell of the tomato rows for an hour and to address the concerns of quieter, more manageable colleagues.”

I don’t know why this woman was getting urgent faxes in 2007, when her book was published, and not, say, urgent emails. I also don’t know if anyone but close friends would ever call Kingsolver “a good time,” because she is so clear in her somewhat mansplain-y tone and unapologetic in her lecturing. But after becoming a mother myself, and needing to step it up in somewhat matronly ways, I don’t always feel like “a good time” is what the world needs more of right now. Instead, I rather enjoyed being chastened by Kingsolver about my food choices and being reminded just how far our country has gotten from being careful stewards of the land. I was also more than happy to be inspired by her ideas about just how much my kitchen habits play a part in correcting that distance.

So the book did change my life in certain ways (you were right, Rick Bass!) because it forced me to pay attention to how I am using my money right now to vote for food systems in our country. Do I make it a point to buy from the farmer’s market, where food is so abundant and cheap it feels criminal not to support the people bringing it to me in bulk? Do I drag myself there on Saturday mornings and talk to real live people selling beautiful fresh food instead of putting up with the zombie apocalypse that is my local grocery store? Do I use all the canned goods gifted to me by industrious friends and family members, valuing the work and photosynthesis packed in those hard-eared rows? Am I embracing food as a way of life, or merely scrambling to survive one hurried meal at a time?

I’ve thought about all this before, of course. I noticed how utterly uninspired the people who work at our grocery store are and despaired when my interactions with them were beyond lackluster. Then I kept going in the same circles, putting up with sub-par food and outlandishly absent customer service because I was lazy, and I’m an introvert, and because the farmer’s market is so intensely crowded and overwhelming with quality choices that every week, about seven minutes in, Samantha pulls me down to her level and whispers in my ear: “I’m ready to go now.”

|

| Hey Kids! Free activity offered by the CHILD EVANGELISM FELLOWSHIP. Run, run, run. |

I get it. It isn’t always easy to do the right thing, and the right thing can also be a rapidly moving mark. But something about Barbara Kingsolver’s tone and wisdom and, I don’t know, gall, is like a coach in the back of my spine right now, pushing me forward to keep exploring food choices and believing in a better way for our country, our bodies, our communities, our local economies.

Animal, Vegetable, Miracle also got me into weeding, which I consider the real miracle being referred to in the book’s title. We don’t have a garden but we do have a beautiful yard that I have no idea how to care for, a fact that gives me no shame. After reading about Kingsolver’s enthusiastic plunges into canning and chopping and making dinner with her family night after night, rolling up her sleeves again and again to accomplish what she’s set out to do, I’m basically unafraid to make mistakes right now: in the dirt or in the kitchen. Traditionally, if I don’t know what I’m doing, then I simply don’t do. But lately, when Samantha drags me out to the yard, instead of insisting we change out of our pajamas first or, I don’t know, do something besides sweep the patio for fun, now I’m all for it. Big honking clippers in hand, dirt under my nails, I suss out what belongs and what doesn’t, enjoying the sun and fresh air as Samantha sits sans trepidation in patches of ivy I’m certain host a few unseen garter snakes and frogs: the id of the world doing its work. Suddenly I am willing to be part of this messy, fertile place.

There are a few books on my desk that I've dog-eared in and out, but I sort of want to break up these mega posts I’ve been writing lately. The ruminative, examining spirit I try to set on SNB is often at odds with the world of giving Samantha breakfast, tap-dancing one step ahead of her toddler-y suggestions, squeezing in runs before dinner, and pretending to give myself some sleep. Lately I’ve been staying up late reading, which is nothing new for me exactly, but I’m sort of amazed by the long stretches of nights I keep doing it. I am a night owl, at heart, but having to be up in the morning for the girl means learning to put myself to bed so I can avoid being an ogre the next day. I’ve been casting my vote for literature the past two weeks, ogre-ness be damned, and while it’s sort of dreamy, it’s also a little strange. After a long, active summer full of sunshine and crisp, wet foods, I think some part of me is so happy to sit for a spell, and that part of me isn’t about to give up the soft throws I wrap myself in, or the stacks of un-read books climbing the tables beside me. That part of me is like: I hope you went to the bathroom before you sat down because it is ON, lady.

|

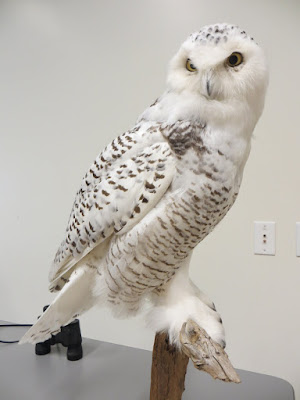

| This bird is dead. For an hour-long presentation I thought it was alive and just intent on studying the audience. |

And now. Let the pumpkin fetish and apple eating begin.

XXOO